|

In

the Global Warming section of this New Scientist's

Magasine website, you can find not only many recent (and old) press

articles about Global Warming but also quite a few quite interesting

and complete reports dedicated to the topic.

A rare collection of information.

Here

are some Headlines

Latest News :

Kyoto

blow : European efforts to save the Kyoto Protocol flounder

as Japan fails to endorse a go-it-alone plan (11 Apr 01)

A

real roasting :

The world condemns Bush for sabotaging climate treaty (7 Apr 01)

Carry

on regardless :

Can the world go it alone if the US backs down on global warming

? (24 Mar 01)

Shattering

the greenhouse :

We have the technology to halt global climate change, so let's use

it

(10 Mar 01)

Recent

Articles about Global Warming (some)

:

Global

Warming : Scientists warn global warming could catastrophically

change the planetary processes that make the Earth habitable (19

Feb 01)

Dead

seas : As temperatures rise, the fate of ocean life hangs

in the balance (13 Jan 01)

High

and dry : Don't blame global warming for every flood (9

Dec 00)

Smokescreen

exposed : A new report suggests the Kyoto Protocol on climate

change is unworkable (26 Aug 00)

Gas

from the past : It took a handful of shells from a mountain

under the Pacific to confirm carbon dioxide's central role in the

drama of Earth's changing climate (22 Apr 00)

The

hole story : Every year, about this time, the air above

the Arctic teeters on the brink of an ozone-destroying frenzy. Just

how bad will it get? Gabrielle Walker braved the Swedish winter

to find out (25 Mar 00)

The

heat is on : Global warming is accelerating faster than

climate modellers predicted (4 Mar 00)

Burning

backwards : Could cunning chemistry keep carbon emissions

in check ? (29 Jan 00)

Global

Warming FAQ :

All you ever wanted to know about climate change

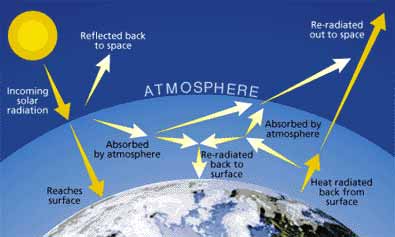

What

is the greenhouse effect?

Warmth

from the Sun heats the surface of the Earth, which in turn radiates

energy back out to space. Some of this outgoing radiation, which

is nearly all in the infrared region of the spectrum, is trapped

in the atmosphere by so-called greenhouse gases. For instance, water

vapour strongly absorbs radiation with wavelengths between 4 and

7 micrometres, and carbon dioxide absorbs radiation with wavelengths

between 13 and 19 micrometres.

The

trapped radiation warms the lower part of the Earth's atmosphere,

the troposphere. This warmed air radiates energy - again, largely

in the infrared - in all directions. Some of the radiation works

its way up and out of the atmosphere, but some finds its way back

down to the Earth's surface, keeping it hotter than it would otherwise

be. This is the greenhouse effect.

Are

water and carbon dioxide all we have to worry about? Are

water and carbon dioxide all we have to worry about?

No.

Other gases can absorb infrared radiation and contribute to greenhouse

warming. These include methane, ozone, CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons)

and nitrous oxide (released by nitrogen-based fertilisers). Of these,

methane is the most important. Its concentration in the atmosphere

has more than doubled since pre-industrial times. Sources of methane

include the biological activity of bacteria in paddy fields and

the guts of cattle, the release of natural gas from landfills and

commercial oil and gas fields, and vegetation rotting in the absence

of oxygen - for instance, in the depths of man-made reservoirs.

Recent studies suggest this last source could be responsible for

up to a fifth of global methane emissions. Molecule for molecule,

other substances are even more potent greenhouse gases. A single

molecule of either of the two most common CFCs has the same greenhouse

warming effect as 10,000 molecules of CO2.

And

the greenhouse effect is a thoroughly bad thing?

Not

quite. Without it, the planet wouldn't be warm enough to support

life as we know it. The problem is that beneficial natural levels

of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are being boosted by human

activities, especially the burning of fossil fuels. If nothing is

done to curb emissions of CO2, for example, the amount of CO2 in

the atmosphere will probably be more than double pre-industrial

levels by the end of the 21st century.

How

do we know what these levels were?

The

most informative measurements have come from bubbles of air trapped

in Antarctic ice. These show that for at least the past 400,000

years, CO2 levels in the atmosphere have closely followed the global

temperatures as revealed in ice cores, tree rings and elsewhere.

If

it's all so precise, why is there so much confusion and uncertainty

about global warming? Surely if we know how much CO2 is entering

the atmosphere and how much energy each molecule can trap, we ought

to be able to calculate the overall warming effect?

It's

not that simple. For example there is no easy formula for predicting

what future increases in CO2 levels will do to the average global

temperature. While we can calculate that a doubling of CO2 in the

atmosphere will force roughly 1 °C warming, the planet is more

complex than that. It could respond by magnifying the effect, but

it could also conceivably damp down the warming. These feedbacks

involve essential planetary processes, such as the formation of

ice, clouds, the circulation of the oceans and biological activity.

What

effects are the main feedbacks likely to have?

One

of the easiest effects to estimate is the "ice-albedo"

feedback. As the world warms, ice caps will melt. As this happens,

water or land will replace parts of the Earth's surface that were

once covered with ice. Ice is very efficient at reflecting solar

radiation into space, whereas water and land absorb far more. So

the Earth's surface will trap more heat, increasing warming - a

positive feedback. Less clear-cut is the impact of the extra water

vapour likely to enter the atmosphere because of higher evaporation

rates. This added water vapour itself contributes to the greenhouse

effect, another positive feedback. But it may also increase cloud

cover. The dominant effect of some low-altitude clouds is to shroud

and cool the Earth - a negative feedback - but other clouds, such

as cirrus, may trap heat at low levels, giving another positive

feedback.

Disputes

about how water vapour and clouds will influence global warming

are at the heart of many of the disputes between mainstream scientists

and the handful of greenhouse sceptics. Overall, the majority view

is that positive feedbacks could amplify the warming effect by perhaps

2.5 times. But some sceptics believe the feedback effect could be

neutral or even predominantly negative.

Why

do sceptical scientists think that? Why

do sceptical scientists think that?

One

reason is that something strange has been happening to warming trends

in the past couple of decades. While ground-level temperatures around

the world have gone up, the warming has failed to penetrate the

atmosphere. The atmosphere has actually been cooling in some large

areas three kilometres above the Earth. According to computerised

climate models, the warming should spread right through the troposphere,

the bottom ten kilometres or so of the atmosphere. Sceptics argue

that if the models are wrong about how surface warming influences

temperatures in the troposphere, they are also likely to be wrong

about the movement of water vapour between the surface and the upper

troposphere. That in turn may mean they are wrong about water-vapour

feedback - one of the vital mechanisms behind global warming.

So

does this mean there are some scientists who don't believe in the

greenhouse effect or global warming?

No,

this is a myth. All scientists believe in the greenhouse effect.

Without it the planet would be largely frozen. And all scientists

accept that if humans put more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere

it will tend to warm the planet. The only disagreement is over precisely

how much warming will be amplified by feedbacks. And there is a

growing consensus that the average global warming of 0.6 °C

seen in the past century - and particularly the pronounced warming

of the past two decades - is largely a consequence of the greenhouse

effect.

|