|

|

|

|

Antarctic Polar Regions | A short History of the Antarctic Antarctic Polar Regions | A short History of the Antarctic

A Continent for Science and Adventure ( Page 2)

|

|

Along the new explorers are the new adventurers

Science has not been alone in attempting to conquer the 6th continent. To a lesser extent and with objectives that are often less laudable and certainly less useful, do-or-die daredevils have also become interested in the Antarctic. Thus far, they have done just about everything: climb Everest in a few hours, walk about at a height of 8,000 metres without oxygen, attempt extreme summits in winter, walk, pedal, fly and sail around the world, explore the most dangerous, deepest and inaccessible abysses, try and reach the North Pole by motorcycle, sailboard, microlight aircraft, on foot with and without assistance, dive deep, very deep, row or swim across oceans, etc. The list goes on. So what is left for them to do? The Antarctic! The final frontier…

The first adventure worthy of the name was achieved by three British adventurers, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Charles Burton and Olivier Shepard, who in the space of 67 days (summer 1980-1981) succeeded in going by skidoo from the Sanae South African base located on the Atlantic coast of the continent to Scott base on the Ross Sea. After the achievement of Fuchs and Hillary during IGY, the trek by Fiennes was the second crossing of the continent in its entirety, but it was the first to be successful without outside assistance. This expedition was part of a far-fetched project dreamt up Fiennes: to go round the world via the poles! There were so many heart-stopping moments along the way, the tale of the British adventurer's experiences (5) has become the stuff of legend among the great polar accounts: in fact, the big difference with the Fuchs-Hillary team - apart from the fact that Fiennes was travelling without assistance - lay in the fact that the men were on skidoos, out in the elements, and so were exposed at all times to the cold, snowdrifts, the wind and terrible blizzards. To read Fiennes's story, you come to realise that the vast majority of the crossing was real hell: crevasses to be avoided (if they could see them), sastruggis that had to be cut with ice-axes to allow the vehicles to pass, glaciers to be negotiated, one hand frozen to the throttle, having to bring the other across in front to free the frozen hand for a moment, paralysis caused without knowing by being in the sitting position and the chafing caused by the wind and the speed of the skidoo, manhandling the machines across difficult areas, handling the ropes, bodies numbed by the cold, hands all puffy, then starting all over again with the sledges, negotiations depressions in the terrain, etc.

It is, of course, impossible to relate the many incidents experienced by everyone who has gone to take on the great white continent. Indeed, in less than a quarter of a century there have been thirty of so expeditions into the high latitudes involving crampons being strapped on to set on the ice of the Antarctic. A recent example: between October 1996 and February 1997 alone, four expeditions attempted to the Antarctic (in its entirety or in part), including one team from Korea, another from Norway, one from Poland and one from France, which went out alone and on foot from the area surrounding the Patriot Hills base (in fact, a tourist encampment) to the South Pole, representing a trek of 1,100 kilometres. So only the major milestones in the history of sporting exploits in the Antarctic are related here. We began with Fiennes, because to some extent the British was inaugurating a sort of new age in Antarctic discovery, the sporting endeavour. Now here is the story of the adventure of the French doctor, Jean-Louis Etienne.

|

|

Jean-Louis Etienne and his fellows's adventure across Antarctica in 1989-90 was one of the most heroïc and demanding odyssey of the modern era of polar regions exploration |

To attract the attention of the media, you always have to have a superlative, something no-one has ever done before. Fiennes had succeeded in making the first crossing without assistance. As for Etienne, he decided that his trip would be the longest every undertaken by man in the Antarctic and that it would be done in the great polar tradition, with sledges and dogs (which have since been banned in the Antarctic - see Madrid Protocol, part IV). Unlike what usually happens with this type of expedition, all of the fuss was made on behalf of a cause: to make the world aware of the problems surrounding the protection of the Antarctic environment at a time when all good intentions stood a good chance of going west with the adoption in 1988 of the Wellington Convention, which provided for the regulation of exploiting the continent's mineral resources. So, accompanied by five men, an American (Will Steger, whom he had met on the way to the North Pole and with whom he dreamt up the expedition), a Briton from the British Antarctic Survey (Geoff Somers), a Russian scientist (Victor Boyarsky), a Chinese glaciologist (Qin Dahe) and a Japanese master of dogs (Keizo Funatsu), Etienne set off from Ilyushin on the Chilean trail from King George Island. A few days later, the six men, tons of equipment and some 40 dogs were taken by Twin Otter to the edge of the Larsen Ice Shelf. Before them lay a trek of 6,000 kilometres that would take them, via the South Pole and the Vostok base, to the Russian base of Mirny. The budget for the expedition was colossal: more than 350 million Belgian francs... Fourteen fuel stops were planned along the way and caches of supplies were left the whole length of the peninsula. The men trained for several months in Greenland. On 11th December 1989, after 134 days of progress over difficult terrain, covering 3,200 kilometres by sledge in appalling weather conditions (blizzards and storms succeeded one another at a relentless rate, sending the mercury plunging on countless occasions to under -50°C), the team finally reached the South Pole. When they started off again, they encountered an area of unusually high sastruggis: over a metre in height instead of 30 to 40 cm! But what was this hiccough when it is compared with all the dreadful suffering the men had to endure throughout this historic crossing that lasted 213 days? A mere bagatelle... In any event, when they arrived, victorious, at Mirny, the conditions in which this great adventure was undertaken served the cause of Antarctica, because there was much renewed talk about the project to create an Antarctic world heritage area.

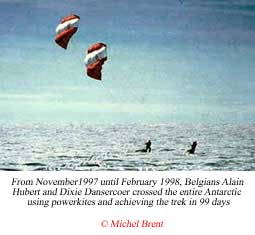

Another great Antarctic adventure was that of Reinhold Messner, the mountaineer who has never flinched before any challenge. He also wanted to make a significant mark for himself and decided to achieve what Filchner and Shackleton had failed to do in 1911-12 and 1914-15: to cross the continent in its entirety, from the Weddell Sea to Scott base. The initial project was somewhat modified on account of the dreadful weather and it was finally from the Ronne Ice Shelf - at 82° latitude south (the Belgians, Hubert and Dansercoer, were to leave even further south) - that Messner, accompanied by the German, Arved Fuchs, left on 1st November 1989. Three months later, after covering 2,400 kilometres and being re-supplied twice, they reached the Ross Sea. The unusual feature of this expedition lay in the fact that they were the first to travel on foot (on skis) pulling their sledges behind them and using a new system of polar traction - the parafoil. It was the same method used by the Belgian expedition South Through the Pole 1997-98 (see the chapter on "To commemorate the centenary of the Belgica"), a sail filled by the wind that pulls along anyone and anything attached to it.

|

South through the Pole expedition conducted by Alain Hubert and Dixie Dansercoer in 1997-98 (former king Baudouin base to McMurdo) was the quickest TransAntarctic trek ever succeeded in history South through the Pole expedition conducted by Alain Hubert and Dixie Dansercoer in 1997-98 (former king Baudouin base to McMurdo) was the quickest TransAntarctic trek ever succeeded in history |

From 1990 onwards, a wide range of other adventurers would set out to conquer the Antarctic continent. As the terrain is immense and relatively unspoilt, lovers of 'world firsts' and other top-notch deeds are able to launch themselves at the place to their heart's content. Erlin Kagge, a Norwegian national, was the first man to reach the South Pole (January 1993), alone, on skis and totally unsupported, from Berkner Island on the edge of the Weddell Sea. In 1992, Fiennes returned to the scene of his exploits and made an attempt with Mike Stroud, from the same location selected by Kagge, to cross the continent in its entirety without any outside re-supplying. They had to give up 500 kilometres from their goal. During the southern summer of 1995-96, no fewer than 6 expeditions tackled the trek from Berkner Island to the South Pole, on foot and unaided (a method of travelling that seemed to become standard at the end of the century); five of them were to succeed. The first to arrive was the Norwegian explorer, Børge Ousland, who became the first man to reach the North Pole three times (1994) and the South Pole alone, on foot and without being re-supplied along the way. Leaving on 7th November 1995, he was to take 44 days to travel the 1,360 kilometres separating him from the pole; in fact, his intention was to go as far as Scott base and thus achieve, under the same conditions, the first crossing of the continent in its entirety. But as he had to give up 80 km from the pole, the insides of his thighs bleeding, it is his exploit to the South Pole that has gone down in history. He would be followed closely by a Pole, a Russian, a Briton and two Canadians. But Ousland, aged 34, is someone who does not give up easily. A year later, he set out from the same place and finally succeeded in reaching the American base of MacMurdo after 64 days of travelling without any major incidents, covering 2,845 kilometres in the same conditions. Which places him at the head of these new polar adventurers who manage to allow their passion to surpass themselves and the need they experience to keep on pushing their limits back even further, while drawing the attention of public opinion towards this far-off corner of the world and making people aware for a good reason: the permanent protection of the Antarctic ecosystem.

|

Women in the Antarctic

If we look at the career of the Belgian scientist, Ghislaine Crozaz, who relates her experience as a researcher working in the United States in the final chapter, we are forced to agree that until the relatively recent past, women were considered as personae non gratae in the Antarctic. Too tough for them, no doubt, the Antarctic had always been a matter for men, with the exception of the Norwegian whalers who at the beginning of the century were happy to take their women along with them and the Russian scientists who, from the International Geophysical  Year onwards, included female personnel in their expeditions (6). But surely these were just two exceptions that confirmed the rule. Didn't Ghislaine Crozaz have to wait many years before being accepted as part of an American expedition that went to look for meteorites on the Antarctic icecap? Year onwards, included female personnel in their expeditions (6). But surely these were just two exceptions that confirmed the rule. Didn't Ghislaine Crozaz have to wait many years before being accepted as part of an American expedition that went to look for meteorites on the Antarctic icecap?

Barely ten years ago, it was the authorities of the British Antarctic Survey that began grudgingly to accept female scientists as part of the personnel at their bases on the Antarctic peninsula, obliging them to take the contraceptive pill before leaving. At the time, this constraint was justified by the fact that a delivery occurring in the dead of the polar night, far from the nearest hospital, could represent a hazard for the woman in question and would be a problem for the other member of the base. Along the same lines, there had been the political incitement of Argentina and Chile to send women to the white continent for the sole purpose of giving birth there and hence giving Antarctic nationality to the newborn baby, which would then be used by the countries if any claims for territorial sovereignty should come under discussion at a later date...

Despite all that, the women had in fact come to the Antarctic to work there. Edith Ronne (wife of Finn Ronne) and Jennie Darlington, both American citizens, were the first women to over-winter in the company of 5 expedition companions on Stonington Island; that was in 1947. Fifteen years later, in 1962-63, American women boarded the Eltanin for a scientific campaign (6). After them came a number of Australian women who were appointed expedition leaders. In 1979, the American Michele Raney became the first woman to over-winter in a scientific base. In 1990, a German team made up exclusively of women (9 in total) spent the winter at the Georg-von-Neumayer base (70°37' latitude south, 8°22' longitude west). Their scientific programme included taking measurements of seismic disturbances, as well as observing the Earth's magnetic field. Five years later, the first mixed German team also over-wintered at Neumayer: the expedition T-shirts boasted "Neumayer goes mixed", accompanied by a logo representing a stork and a baby! As far as Belgian female research is concerned, we will in any case see in the final chapter that it couldn't be in better shape.

As for sporting achievements, and even though there have been fewer women willing to take on the thrills of the Antarctic, they have always shown that they are up to the task. First, in 1986-87, there was the Norwegian glaciologist, Monica Kristensen, who set out along the historic route (1911) of Amundsen with dogs. She had two companions with her; all three had to do an about-turn 440 kilometres from the South Pole. In 1992-93, an expedition made up of women only (Americans), led by Ann Bancroft, reached the South Pole, on foot and on skis, having been re-supplied a number of times. A year later, Liv Anersen, a Norwegian, succeeded in reaching the South Pole after 49 days of travelling without assistance. Finally, more recently, in December 1996, the French climber Laurence de la Ferrière succeeded in completing the same exploit, re-supplied just once along the way. |

(5) Ranulph Fiennes, Mind over Matter, the epic crossing of the Antarctic continent, Sinclair Stephenson, 1993

(6) G.E. Fogg, A History of Antarctic Science, Studies in Polar Research, Cambridge University Press, 1992, p 152-53.

|

South through the Pole expedition conducted by Alain Hubert and Dixie Dansercoer in 1997-98 (former king Baudouin base to McMurdo) was the quickest TransAntarctic trek ever succeeded in history

South through the Pole expedition conducted by Alain Hubert and Dixie Dansercoer in 1997-98 (former king Baudouin base to McMurdo) was the quickest TransAntarctic trek ever succeeded in history Year onwards, included female personnel in their expeditions (6). But surely these were just two exceptions that confirmed the rule. Didn't Ghislaine Crozaz have to wait many years before being accepted as part of an American expedition that went to look for meteorites on the Antarctic icecap?

Year onwards, included female personnel in their expeditions (6). But surely these were just two exceptions that confirmed the rule. Didn't Ghislaine Crozaz have to wait many years before being accepted as part of an American expedition that went to look for meteorites on the Antarctic icecap?