See also our comparative map of the

Arctic expeditions of spring 2002

Monday 8 July

Monday 8 July

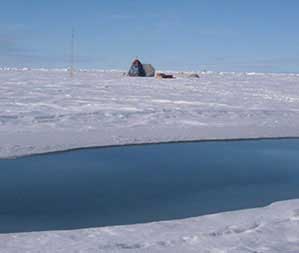

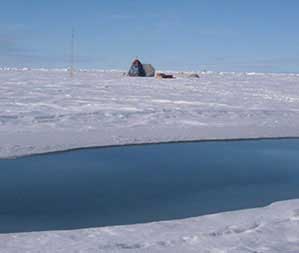

Jean-Louis Etienne spent the final few days of his adventure on the Arctic Pack dismantling the instruments and scientific equipment, and packing his personal effects. That job was finished on Sunday 30 June. These final weeks of the expedition were characterized by the constant presence of bad weather (between 10 and 26 June, JL almost never saw the sun) and by the melting ice, of course. 30 June: "The Polar Observer is like an islet perched in the middle or a crown of water. Now I am wearing boots, because there is up to 20 cm of water in places". 27 June: "The Polar Observer is practically surrounded by melt-water. Any step in the snow ends in water. On the lower areas of the ice floe, the snow has almost disappeared, revealing expanses of surface water in the process of forming. Water, nothing but water. I will be leaving the ice floe during the summer period when it will become impracticable".

Since then, the French explorer has been waiting for the ice-breaker, the Yamal, which is due to pick him up en route for a tourist cruise to the North Pole (see the site of Adventure Associates). The ice-breaker is due to leave Longyearbyen (Spitzbergen) on 9 July and reach the North Pole two days later, on 10 or 11 July. On his site, JL writes that the departure from Spitzbergen should happen on 4 July.

Whatever the case may be, the ship should not come too close to the place where Etienne is, because it breaks up all the ice in its path. So it will be an MI8 helicopter which will helihoist the capsule, the man and his dog.

Tuesday 25 June

Tuesday 25 June

With a fortnight to go until he is picked up by a Soviet ice-breaker, Jean-Louis Etienne continues drifting aboard the Polar Observer. As the scientific experiments are all set up now, the French doctor has time to write and think about the future of the world and the sources of energy that will need to be developed in the future. In his communication on Thursday 20 June, he wrote: "Hydrogen looks to be the ideal energy source for transport. Silent engines producing a harmless waste product, water. Prototypes are already running in Germany, the United States and the Scandinavian countries. There are questions about the cost of production, storage and distribution to be resolved before hydrogen can replace hydrocarbons in a few decades' time".

From time to time, Etienne, who is a great storyteller, reminds visitors of the essential notions like those of the greenhouse effect which he described on Tuesday 11 June: "We hear nothing but bad new about the atmosphere: the air has become unbreathable, the greenhouse effect is getting worse all the time, and the hole in the ozone layer is far from closing again. The air is sick of our civilization, and it is time to wake up. Without that layer of air that surrounds our planet, life would be impossible, for two essential reasons:

I- the atmosphere provides the OXYGEN that we breathe

II- the atmosphere creates a PROTECTIVE ENVELOPE around the Earth thanks to two phenomena: retention of the heat from the sun, and the protective shield

- Retention of the heat from the sun: the greenhouse effect on the Earth's surface, where air acts like a window that allows the sun's rays to pass through, and prevents the heat from leaving again - that is the greenhouse effect, which is familiar to market gardeners everywhere for protecting their crops. The greenhouse effect is therefore a natural phenomenon which is essential to life. Without that, the temperature at the Earth's surface would be very cold, -18°C, there was be no liquid water, nor plants, nor animals, and they would never have been able to exist. Today, we talk about global warming because the greenhouse effect has increased due to all our gas discharges: carbon dioxide, industrial emissions, methane from fermentation and other particles;

- The protective shield: the air is a filter that stops all the rays that are dangerous to life. The best-known of these filters is the ozone layer, that rare and natural gas of the upper atmosphere, which cuts out certain ultraviolet rays that are toxic to living cells (and which should not be confused with the ozone created by urban pollution).

The immensity of the sky gives the impression that air extends to infinity, as far as the stars. In fact, the atmosphere is a very fine layer, a few kilometres thick, the equivalent of a layer of cellophane stretched around a pumpkin. Its ability to absorb pollution has reached limits that we can feel: breathing difficulties in the cities, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer. Here at the North Pole, the photometer and flowmeters that I have installed on the ice-floe measure the transparency of the sky, the flows of solar radiation, particularly the ultra-violet rays, for the researchers at the Atmospheric Optics Laboratory in Lille. Even this far away from civilization, we find traces of our atmospheric pollution. The sky is being poisoned, and those are not words that I have plucked out of thin air".

The immensity of the sky gives the impression that air extends to infinity, as far as the stars. In fact, the atmosphere is a very fine layer, a few kilometres thick, the equivalent of a layer of cellophane stretched around a pumpkin. Its ability to absorb pollution has reached limits that we can feel: breathing difficulties in the cities, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer. Here at the North Pole, the photometer and flowmeters that I have installed on the ice-floe measure the transparency of the sky, the flows of solar radiation, particularly the ultra-violet rays, for the researchers at the Atmospheric Optics Laboratory in Lille. Even this far away from civilization, we find traces of our atmospheric pollution. The sky is being poisoned, and those are not words that I have plucked out of thin air".

Every day, Etienne finds an interesting subject (the movement of the ice floe, the Coriolis force, global warming, the thaw, his encounters with seabirds, rain at the North Pole, the Kyoto Protocol, etc.) to fill his log, a log which will be published in the form of a book after the expedition.

His latest position, as of Tuesday 25 June 2002. N 86°50 839 . E 5°06 229

Friday 7 May

Friday 7 May

The major fact in the last 15 days of his expedition is that Jean-Louis Etienne and his crew (capsule and Lynet, the dog) are to some extent marking time when they are not actually going backwards. "The South Wind is constantly against me. Over 36 hours", Jean-Louis wrote on 23 May, "it has cost me a week by driving me northwards. It is harassing me and torturing my mind, whereas not a lot would be needed to damp down my impatience to see it dropping: just to accept the simple idea that it is at home here."

We left the French explorer on 24 May at 87°57 N / 14°18' E: we now find him again, 15 days later, at 88°08' / 16°124 E, or only a few minutes further to the North! The unforeseen movements of the pack ice and especially the persistent and odd presence of a South Wind have been complicating matters for the Mission Pack-Ice Expedition.

Apart from this setback, Jean-Louis is on marvellous form. The rise of the mercury and the melting of the ice goes on: in the evening of 24 May, Etienne recorded a record temperature of +1°C with a humidity rate of 96%. Which creates something of a heavy atmosphere in the capsule.

Furthermore, he seems to have made a relatively interesting discovery: a layer of warmer water at a depth of about 400 metres. He is unaware, however, of how important this discovery might. While waiting, Etienne continues his scientific observations, but he has lost an important instrument, his sampler for measuring the thickness of the pack ice.

Friday 24 May

Friday 24 May

Jean-Louis Etienne is continuing his drift southward in the company of his dog Lynet. Last Wednesday, which was the last day when his site was updated, he had already drifted 2°45' southward following roughly the same route as planned before the trip. That represents a distance of approximately 280 kilometres since his departure on 15 April.

Lynet the dog

Lynet the dog |

You have to admit that it is really cosy inside his capsule. "It was between 17 and 21°C inside the Polar Observer while it was -15°C outside, wrote Jean-Louis on Monday 6 May. Which enables the explorer to attend to his business as an observer, and perform a large number of scientific experiments. He is measuring the thickness of the ice. This is how he does it (extract from his diary of 21 May): "The afternoon was devoted to measuring the developments in the ice thickness: it was 2.35 metres thick last week.

I decided to film the manoeuvre. I know now that filming yourself doubles the time you take to do anything, it is a job within a job. Drilling through the ice floe took 45 minutes, but I only filmed for about 10 minutes, making regular round trips between the hole and the camera. I filmed the initial pictures from a distance, because I started the drilling perched on a box to be able to manoeuvre this auger which is 2.5 metres tall. As the tool went further in, I brought the camera closer, which means: levelling the tripod, re-framing the shot and returning so that I was in shot. Finally, after easily 1½ hours, I brought the lens close to the hole to film the final scene, the water gushing from the ocean once the ice sheet had been pierced.  Unfortunately, the metal rod of the auger broke shortly before that, leaving the tool at the bottom. It took an hour's patience fishing around in that dark hole 12 cm across. It was starting to get stuck in the ice, and I was afraid I would lose it. After examining the situation, I joined the two pieces of the shaft of this old-fashioned (and clever) Russian tool with the equipment I found on the spot. It was seven in the evening, and I decided to postpone the remaining activities to the next day, if the repair proved effective".

Unfortunately, the metal rod of the auger broke shortly before that, leaving the tool at the bottom. It took an hour's patience fishing around in that dark hole 12 cm across. It was starting to get stuck in the ice, and I was afraid I would lose it. After examining the situation, I joined the two pieces of the shaft of this old-fashioned (and clever) Russian tool with the equipment I found on the spot. It was seven in the evening, and I decided to postpone the remaining activities to the next day, if the repair proved effective".

He is calculating the speed of the drift: "I calculated the speed of my drift over several days of constant wind", he wrote on 13 May. Between 7 May at noon and 12 May at noon, the average wind speed was 20 km/h and I travelled 26 minutes of latitude, or 26 nautical miles, or 48 km in 5 days, which gave an average speed for the drift of 0.4 km/h. This calculation confirms that the ice-floe is drifting at 2% of the wind speed".

He lowered (by hand) a depth probe over 600 metres down to make oceanographic measurements.

Lowering the depth probe

Lowering the depth probe |

He regularly tries his hand at fishing (of course, this is rather less scientific) by lowering a hook and line through the hole in the plankton net, but without any result so far.

His position on 23 May halfway through his adventure (Etienne should be picked up on 4 July by the Yamal, a Russian ice-breaker:: 87° 57' N / 14° 18' E.

Saturday 04 May

Saturday 04 May

On his website, Jean-Louis Etienne recounts in the smallest detail the scientific measurement operations that he performs throughout his daylight hours. The account is fascinating in that the work seems to be both useful in scientific terms and also interesting to do. Here is an extract from Thursday, 02 May :

I must explain to you how, with rudimentary means, one can conduct biological oceanography, i.e. the study of life under the pack ice. Make a hole in the ice with a diameter of 1m (chain saw, pick and shovel). Vertically above the hole, place a tripod made of three stakes of wood bound together with a rope. Suspend a pulley and pass a ball of string through it that you unwind to its very end (150m). Attach the far end with a skewer of ice and return to the hole. Attach the plankton net and its 5kg-weight to the end of the string beneath the  pulley and immerse the whole thing. The string stretches under the weight. Go back to the far end of the string, fasten it to your belt and slowly return towards the hole, at the speed that the net is descending. When you get to the tripod, the net is suspended beneath the surface at the end of a 150-metre piece of string. That is the time to bring it back up again. Turn round and pull, shoulders forward and in a straight position like a carthorse, as far as the ice skewer where you have attached the string (be careful that it doesn't get away from you). When you turn round, you will see in the distance the net suspended beneath the tripod. The walk back seems to be extremely light and gives you time to cudgel your brains about the harvest. Not much is known about life in this ocean, so everything is open to the imagination.

pulley and immerse the whole thing. The string stretches under the weight. Go back to the far end of the string, fasten it to your belt and slowly return towards the hole, at the speed that the net is descending. When you get to the tripod, the net is suspended beneath the surface at the end of a 150-metre piece of string. That is the time to bring it back up again. Turn round and pull, shoulders forward and in a straight position like a carthorse, as far as the ice skewer where you have attached the string (be careful that it doesn't get away from you). When you turn round, you will see in the distance the net suspended beneath the tripod. The walk back seems to be extremely light and gives you time to cudgel your brains about the harvest. Not much is known about life in this ocean, so everything is open to the imagination.

Like the last time, with a great deal of excitement, I opened the bottom of the net into the basin and nothing came out. A piece of ice was blocking the collector. I knocked it against the bottom of the basin to unblock it and broke the basin. Almost all plastic materials are fragile at low temperatures. I returned to Polar Observer to dissolve the ice on the net and to glue the pieces of the basin together again (it's the only one that I have). Test to be postponed until tomorrow. Here, nothing can be taken for granted, and the devil is in the detail.

Apart from that, Jean-Louis is feeling fully at ease in his cocoon, Polar Observer. On May 3 in evening, it was -18°C outside and +17° C inside at the height of his face and +12°C at the level of his feet, although the heating had been off for 18 hours. It should be known that the walls of Polar Observer contain a 15cm-thick insulating foam, a superb illustration of the use of solar energy for heating.

Apart from that, Jean-Louis is feeling fully at ease in his cocoon, Polar Observer. On May 3 in evening, it was -18°C outside and +17° C inside at the height of his face and +12°C at the level of his feet, although the heating had been off for 18 hours. It should be known that the walls of Polar Observer contain a 15cm-thick insulating foam, a superb illustration of the use of solar energy for heating.

His position on 03 May: 89° 05 ' N / 06° 30 ' E. Since the day of its departure, April 15, Polar Observer has therefore drifted 102km in 18 days. Average: 12.75km per day…

Lynet, the Eskimo dog accompanying him on his journey, is on carcking form.

Friday 12 April

Friday 12 April

Jean-Louis Etienne arrived at the Barneo base on the evening of Monday 8 April. Three days later, he was transported in an MI 8 helicopter to the North Pole.

During those three days, he has assembled his Polar Observer capsule and took part in a major TV programme in the Thalassa series (which will be broadcast on 19 April). This weekend, Jean-Louis will be checking together with two technicians that the measuring devices are working. A photographer is also on the spot.

He should be alone for his adventure from Monday.

Friday 12 April / 11-04-02 Review 11/04/2002

Friday 12 April / 11-04-02 Review 11/04/2002

HIS FIRST PRESS RELEASE: news of Jean-Louis Etienne by Elsa Peny.

Today at noon, Jean-Louis Etienne and his capsule will be airlifted by helicopter to the North Pole, and the expedition can start!

You have to earn any great adventure, and he has had quite a few mishaps on the way to the Pole. First of all, there was the bad weather that prevented Jean-Louis Etienne and his fine team from reaching the Russian station of Barneo, where the assembly of the capsule and the setup of all the scientific equipment were planned.

They were stuck in Spitzbergen, and began a long wait. The news was bad: at Barneo, the runway was cracked, and the bulldozer that was supposed to repair it had fallen down a crevasse.

Then it was the turn of the Russian administration to interfere: the pilot of the Antonov 75, a Russian-built aircraft, with a very large cargo capacity, and which was to transport the capsule, is Ukrainian. The base were categorical about it: he needed an authorisation to land. This disagreement would not take very long, because it is an international zone.

After a three-day delay, on Monday evening, Jean-Louis Etienne and his team reached Barneo. As if all of that was not enough, their first night at 89 North was spent with no heating!

The next day, the team pulled out all the stops, everyone pitched in, and the capsule was fully assembled by noon on Wednesday. The weather is fine: not a breath of wind, but still -38°C.

The immensity of the sky gives the impression that air extends to infinity, as far as the stars. In fact, the atmosphere is a very fine layer, a few kilometres thick, the equivalent of a layer of cellophane stretched around a pumpkin. Its ability to absorb pollution has reached limits that we can feel: breathing difficulties in the cities, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer. Here at the North Pole, the photometer and flowmeters that I have installed on the ice-floe measure the transparency of the sky, the flows of solar radiation, particularly the ultra-violet rays, for the researchers at the Atmospheric Optics Laboratory in Lille. Even this far away from civilization, we find traces of our atmospheric pollution. The sky is being poisoned, and those are not words that I have plucked out of thin air".

The immensity of the sky gives the impression that air extends to infinity, as far as the stars. In fact, the atmosphere is a very fine layer, a few kilometres thick, the equivalent of a layer of cellophane stretched around a pumpkin. Its ability to absorb pollution has reached limits that we can feel: breathing difficulties in the cities, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer. Here at the North Pole, the photometer and flowmeters that I have installed on the ice-floe measure the transparency of the sky, the flows of solar radiation, particularly the ultra-violet rays, for the researchers at the Atmospheric Optics Laboratory in Lille. Even this far away from civilization, we find traces of our atmospheric pollution. The sky is being poisoned, and those are not words that I have plucked out of thin air".

Unfortunately, the metal rod of the auger broke shortly before that, leaving the tool at the bottom. It took an hour's patience fishing around in that dark hole 12 cm across. It was starting to get stuck in the ice, and I was afraid I would lose it. After examining the situation, I joined the two pieces of the shaft of this old-fashioned (and clever) Russian tool with the equipment I found on the spot. It was seven in the evening, and I decided to postpone the remaining activities to the next day, if the repair proved effective".

Unfortunately, the metal rod of the auger broke shortly before that, leaving the tool at the bottom. It took an hour's patience fishing around in that dark hole 12 cm across. It was starting to get stuck in the ice, and I was afraid I would lose it. After examining the situation, I joined the two pieces of the shaft of this old-fashioned (and clever) Russian tool with the equipment I found on the spot. It was seven in the evening, and I decided to postpone the remaining activities to the next day, if the repair proved effective".

pulley and immerse the whole thing. The string stretches under the weight. Go back to the far end of the string, fasten it to your belt and slowly return towards the hole, at the speed that the net is descending. When you get to the tripod, the net is suspended beneath the surface at the end of a 150-metre piece of string. That is the time to bring it back up again. Turn round and pull, shoulders forward and in a straight position like a carthorse, as far as the ice skewer where you have attached the string (be careful that it doesn't get away from you). When you turn round, you will see in the distance the net suspended beneath the tripod. The walk back seems to be extremely light and gives you time to cudgel your brains about the harvest. Not much is known about life in this ocean, so everything is open to the imagination.

pulley and immerse the whole thing. The string stretches under the weight. Go back to the far end of the string, fasten it to your belt and slowly return towards the hole, at the speed that the net is descending. When you get to the tripod, the net is suspended beneath the surface at the end of a 150-metre piece of string. That is the time to bring it back up again. Turn round and pull, shoulders forward and in a straight position like a carthorse, as far as the ice skewer where you have attached the string (be careful that it doesn't get away from you). When you turn round, you will see in the distance the net suspended beneath the tripod. The walk back seems to be extremely light and gives you time to cudgel your brains about the harvest. Not much is known about life in this ocean, so everything is open to the imagination. Apart from that, Jean-Louis is feeling fully at ease in his cocoon, Polar Observer. On May 3 in evening, it was -18°C outside and +17° C inside at the height of his face and +12°C at the level of his feet, although the heating had been off for 18 hours. It should be known that the walls of Polar Observer contain a 15cm-thick insulating foam, a superb illustration of the use of solar energy for heating.

Apart from that, Jean-Louis is feeling fully at ease in his cocoon, Polar Observer. On May 3 in evening, it was -18°C outside and +17° C inside at the height of his face and +12°C at the level of his feet, although the heating had been off for 18 hours. It should be known that the walls of Polar Observer contain a 15cm-thick insulating foam, a superb illustration of the use of solar energy for heating.